Despite an obvious and completely warranted devotion to their four daughters, it never occurred to my parents to vet the neighborhood before building a house on Woods Road. We’d end up having friends on our street, or we wouldn’t. Either way we’d live and perhaps even prosper.

And if we didn’t, oh well.

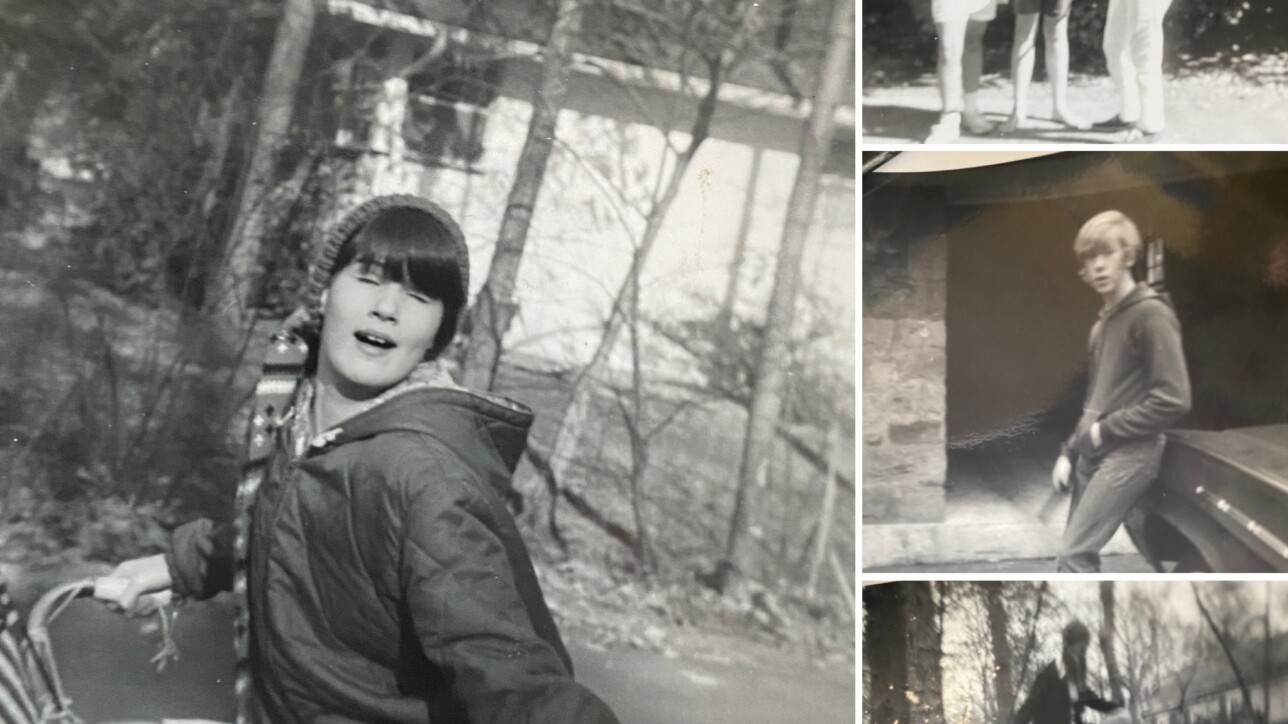

But fate was in our favor. Woods Road was an elongated horse-shoed enclave of forty houses varying in size, shape and personality. And within those houses were kids, so many kids, who spilled from kitchen doors into Four-Square games, Capture the Flag battles and bicycle races up and down the steep hill that really wasn’t very steep at all.

Because of the dense concentration of fun per capita, kids from adjacent neighborhoods emerged from the wooded lot next to the Bishop’s house, cut through the Siefert’s backyard, crossed over Station Avenue and found their way to Woods Road.

And so, the Neighborhood Gang grew and prospered.

Together we epitomized the last great generation of free-range children, reveling in the rumpus of spontaneous softball games, fearless fraternizing and unscheduled entertainment. We lived before helicopter parents sharpened their blades, before SAT tutors charged $100 an hour, before teachers got fired for drinking with students on senior class trips in the Bahamas.

It was a childhood spent walking to Perkel’s Pharmacy for a five-cent candy bar, of calling phony numbers from party-line telephones and of climbing backyard tree houses built by our fathers. It was a time of holding séances in one musty basement and playing ping pong in another. Of rushing outside the second dinner was over and running in packs until dark. We lived in the day when we could (and wanted to) deliver newspapers at ten years old, babysit at 11 and work at the movie theater at 15.

It was when a teenaged boy could expose his male member to 12 year-old girls – repeatedly – without fear of parents finding out, let alone being registered as a sex offender. When pulling the fire alarm in school was considered a prank, not a precursor to incarceration. It was when friends, not parents, picked you up and bailed you out.

We left for college in wood-paneled station wagons filled to the gills with ragged bedspreads, threadbare towels and boxes and boxes of record albums. We went to law schools and medical schools and party schools. We came home for holidays on the Greyhound bus, or with a random stranger found on the ride board. And we always met at Schaeffer’s house on Thanksgiving Eve to boast about our new adventures.

We grew up. We fell in and out of love. We tolerated unfathomable boyfriend and girlfriend choices — but the ones who lasted, we embraced as our own. Some of us got married. Some of us had kids. Some of us found success. Some of us are still looking. Some of us stayed close. Some of us moved away. But we all find our way back.

Last weekend more than a dozen of us got together under the guise of Kit coming in from Seattle. But the real reason was to lend some levity to a founding father with a disturbing diagnosis and a surgery looming. In the course of conversation that ran the gamut from long-dead dogs to long-living mothers, it struck me, not for the first time, that we are indeed a lucky bunch.

I know that in the grand scheme of things we’re not so different from most people our age. Boomers near and far lament the same loss of innocence – not to mention hair, hearing and health. Our coming-of-age stories are interchangeable; the risks we took, the dreams we had, the unyielding belief that we had limitless years of life ahead.

But what makes us remarkable is that no matter how old we’ve gotten, how far we’ve gone, how infirm, incompetent or incorrigible we’ve become, we still haven’t outgrown the Neighborhood Gang.

And at this stage of the game, it doesn’t look like we ever will.