I am a memory hoarder.

So much so that I have notebook after notebook filled with my life’s details, including New Years’ Eve in Moscow, phony number fun and foibles with Margaret, honeymooning in Montreal, singing karaoke in Manilla, bicycling in France and just about every hope, dream, victory and vice I ever combatted throughout my high school career.

I have charts recording the fluid that came from the drains in my chest after my double mastectomy, the number of steps I took, and when, and how much it hurt, after each of my joint replacements, and how much I weighed every single week of my adult life.

I have scraps of paper with profound statements that have changed my life, prize emails saved from the hundreds of thousands my friend Laura and I have exchanged since 1990, lists of names and descriptions of people Patty and I have loved, for a week at a time, on cruise after cruise, and a file cabinet with folders marked Memories, Things to Remember, and since I’ve been a mother, Fun Kid Stuff.

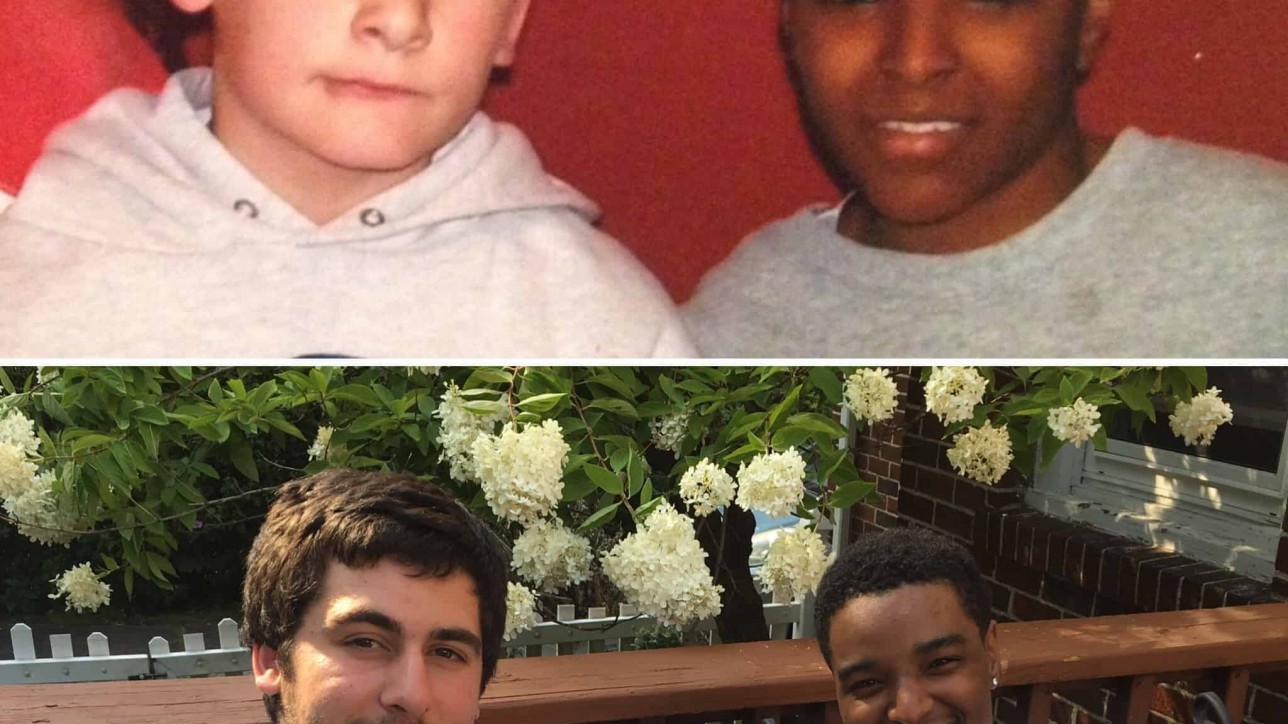

Which is where, when looking for nothing in particular, I found a conversation that took place, in the brand new minivan, between my son, Leo, and his best friend, Koree. It was July, 2005 and they were nine years old.

Koree:

Me and Leo are best friends.

Me:

Do you think you’ll be friends for your whole life?

Koree:

Nah. Cause we’re going to go our separate ways. Leo’s going to be a professional baseball player and I’m going to be a professional basketball player.

Me:

Well, you can certainly still stay friends!

Koree:

No. Cause when we split up, he’ll be in Baltimore and I’ll be in Dallas.

Leo:

I know. We’ll write each other’s names down so we’ll remember each other.

Koree:

But we’ll need a cell phone.

Leo:

When Koree’s famous, I’ll go backstage because I’ll be like Barry Bonds and I’ll get in for free.

When I was nine years old, I had been a published author for two years, having my “Christmas is a time of giving, and I’m so glad that I am living,” second-grade poem printed in the Oreland Sun. For as long as I can remember, all I ever wanted to do was be a writer.

And write I did. I recorded everything I did and said and heard and witnessed with the hopes of one day twisting and turning those phrases and fragments into the Great American Novel. And in the meantime, I wrote short stories and poems, and love letters to my friends. I wrote speeches and eulogies, and long-winded yearbook homages. I wrote toasts and tributes, and silly little birthday ditties.

When I was in 11thgrade, Ms. Scott, said my writing style reminded her of Lillian Hellman, which prompted me to devour every one of the famous author’s plays and memoirs. When I was asked to read one of my pieces aloud at Creative Writing Night, I had to sheepishly admit to a tearful audience, that the story about my dead sister was purely fiction.

In a journalism class in college, realizing I was about to miss a deadline, I whipped up the story of how we pulled off the old bucket-of-water-perched-precariously-outside-the-detested-resident-assistant’s-dorm-door caper. The feature story was published in the school paper and we were caught, perhaps precipitating our subsequent visit to the Judicial Board.

I majored in Advertising, with a concentration in copywriting and a minor in Creative Writing. When I graduated, I was an insecure college graduate with no paid writing experience, so spend ten years in related, but unfulfilling fields, working harder on making friends than making a buck. After I got married and moved to New Jersey, I landed a job at the new cable station, CNBC, as an administrative assistant in the marketing department. Had it not been for the faith of my boss-turned-friend, Caroline Vanderlip, to this day, l may never have had made a dime penning my words.

But, my dream never included writing brochures about how to read a stock ticker tape, or ads touting Maria Bartiroma as the first woman to report from the floor of the NYSE. Though I must admit I did have fun writing promo spots for Geraldo Rivera, trembling my way through an interview with Phil Donahue, and dodging the late, great Roger Ailes.

My career evolved from CNBC to freelance writer, working from home, playground benches or baseball bleachers. I crafted all kinds of copy for all kinds of companies, but still, it wasn’t what I had envisioned back in Mrs. Baker’s second grade classroom.

And, so I wrote my novels. Three of them. One about a bunch of families navigating their way through the 12 year-old travel baseball world. Another about a 30 year-old looking for love in all the wrong places, and the last about four college friends who reunite for a week on a cruise ship. They say always write what you know.

Novels, plural, complete. I did it.

Except that they’re all three still sitting in my computer, afraid to come out, afraid to face the world, afraid to become a dream come true.

Back in 2005, Koree and Leo both played baseball, basketball and football. But within a few years, they had each committed fully to their sport of choice. Leo to baseball, Koree to basketball. They never balked, they never wavered; they were all in. They traveled the country playing in national tournaments, showcasing their skills and picturing themselves first in UNC jerseys and then in whatever pro uniform they were paid to wear. They played hard through high school and into college until their pro ball dreams came to an end.

“Did you ever think of coaching?” I recently asked Koree, who is now in the throes of job hunting.

“Never!” he exclaimed. “I don’t want anything to do with basketball ever again.”

Leo nodded in solidarity.

And that hurt my heart.

Not because of the thousands of hours they devoted to the game. Not because of the tens of thousands of dollars we pumped into the sport. Not because of the millions of dollars they wouldn’t make.

But, because, like their parents before them, they, too, had unfulfilled dreams.

I thought not just about myself and my unsubmitted novels; I thought about Koree’s father who had big dreams of his own. As a college hoops star, he went up against the likes of Michael Jordan and Kenny Smith, who even gave him a shout out while commentating the NCAA tournament.

I couldn’t help but wonder how different all our lives would be if he, or I, or the both of us, had “made it.” What if our DNA had just a little more drive, a little more confidence, a little more talent?

For one thing, Koree and Leo would never have met. He, or we, would be living in different towns, in bigger houses, running in different circles. Instead, we co-raised five pretty decent athletes, who someday, somewhere, will lead their adults leagues in base hits and buckets. They say they won’t, but they’ll coach their kids in cheerleading and soccer and softball.

I picture ourselves, in the not so distant future, gathered for a Hargraves-Voreacos family dinner. There will be a spouse, or five, at the table, a bunch of grandkids in tow. We’ll get to talking about the good old days – the coulda, woulda, shouldas.

Looking around the table, soaking in the love and laughter, we old folk will finally come to terms with our lives. We’ll realize that, despite all of our missed shots, we still ended up with a winning season.

And that is, indeed, a dream come true.